The roses of the school year have begun to bloom.

In Island of the Blue Dolphins, robust village life on the island falls apart after the villagers are attacked by enemies. Food is scarce, and their lives are in danger. They decide to leave their dying home and begin again somewhere new. As the ship that has come for them departs, Karana—the main character—discovers that her six-year-old brother, Ramo, is not on board. Since the death of their parents, she has become the closest thing he has to a mother, even though she is only twelve. She sees him waving from the top of a cliff on the island. A storm is rolling in. She begs the captain to stop the ship, to wait, to do something, but it continues steadily along its course. Without hesitation, she jumps off the ship as it leaves, despite the hands of everyone she knows trying to hold her back. Knowing full well what it could mean for her own survival, she returns to the island to protect him—to stay with him on the seemingly haunted island, where wild dogs roam and food is scarce, until the ship returns. If it returns.

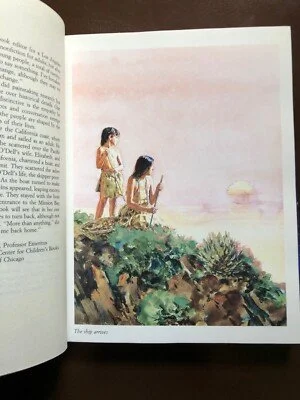

The image of Karana leaping off the ship, in the midst of the impending danger of an approaching storm, is one I ask my students to close their eyes and imagine. I ask them to imagine a painting of the scene, lovingly created by an artist who wishes to portray the love and protectiveness of that moment. I ask them to make decisions about every part of that image in their minds. What does the ship look like? What does Karana’s face look like? What do her fellow villagers look like as they reach out to her, in the vain attempt to stop her? What color is the sky? How turbulent are the waves? Can you see Ramo on the shore? What does he look like?

When I ask them to tell me the answers to these questions, I have found that they almost always say the same things, even year to year.

The ship is gigantic and heroic. It is the rescuing ship, taking these weary people to a new land. They describe the shining sails and the strong wooden planks of the exterior.

Karana is always described as calm. She knows she is doing exactly what she must. Her face is solemn and unsmiling, but not sad. Never sad, scared, or angry. They imagine her mid-dive, just as she is reaching the height of her leap.

The villager’s faces bear horrified expressions—mouths agape, hands outstretched.

The sky and sea are wind-torn and turbulent—Karana’s hair is blown aside, whipping in the wind. The sea foam slams against the side of the rocking ship.

“At that moment I walked across the deck and, though many hands tried to hold me back, flung myself into the sea.”

Ramo appears, standing on the shore, looking uncomfortable and small. He is sorry he caused trouble, just so he could return to the village and retrieve his spear. He sees now how foolish that was, and he is embarrassed. His shoulders are slumped and he is just so tiny. My students always repeat his size, which I find telling and sweet.

This image, created and reinforced by my students year after year, stands as a picture of love and protection.

When Karana arrives on shore, her brother embraces her, and tells her how happy he is to be on the island, just the two of them. Her anger at his foolishness melts away as she holds his smallness in her arms.

While we don’t know the full details of this particular incident, this story is based on a true one. A young woman who was being saved from an island off the coast of California did in fact jump off of the ship that was rescuing her, in the middle of a storm, in order to return to the island. The historical evidence is scant, but perhaps the real Karana did leap off the ship in a gesture of love and protection.

In literature class, we plant roses so thistles may not grow. This rose is one of my favorites. Love is the greatest rose of all.